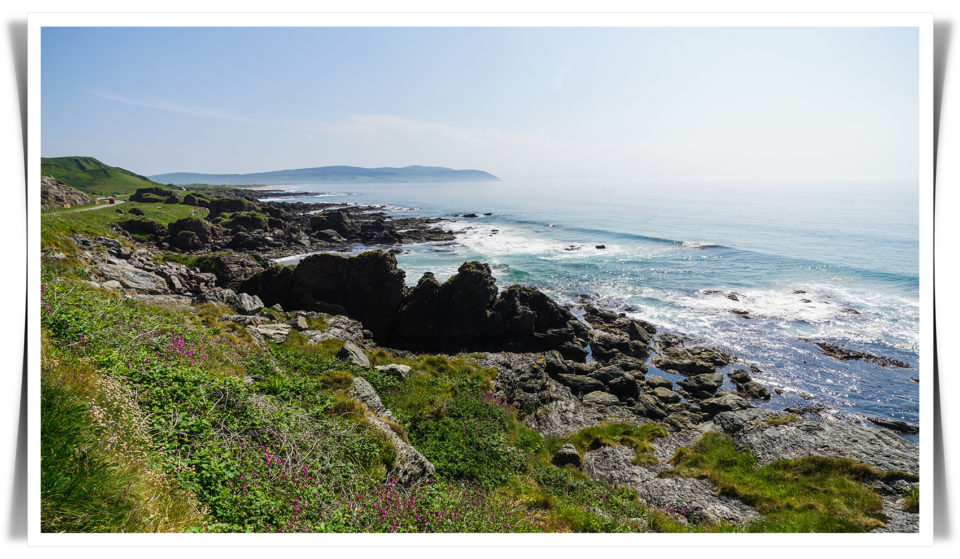

Even now, I struggle to describe just how beautiful Kintyre is – especially in summer. Life bursts out of every part of the landscape. Colours seem richer and deeper here than they are anywhere else I’ve ever been.

Let’s go on a journey from Ayrshire to Largieside.

You begin by driving northeast on the undulating A737 over shallow hills, past cows and sheep and old farms and wind turbines, through the little town of Dalry and into bustling Linwood. There, you join the M8 and get lost in traffic for a while before merging onto the A898 and passing over the swollen Clyde on the Erskine Bridge. Glasgow is a busy place, isn’t it.

After you leave the city, the route gets simpler. You turn onto the A82 and travel northwest, through Dumbarton and into Loch Lomond territory. All of a sudden, things seem much prettier. A long, blue lake cascades along to your right, sun pouring warm light over the mountains on its easterly side.

You pass the turnoff for Luss and continue on past Inverbeg and Stuckgowan before turning left onto the smaller A83. There, the road winds down into the little village of Tarbet (“narrow isthmus”), which sits at the bottom of a low valley between Loch Lomond and Loch Long. Roughly 750 years ago, a band of charming Viking raiders pulled their longships out of the sea at Arrochar on Loch Long and dragged them a mile and a half to Tarbet so that they could raid settlements along Loch Lomond.

Arrochar and Tarbet together represent something of a border between public transport options in Argyll and Bute and those in the rest of Scotland. People travelling by train have to disembark at Arrochar and hitch a ride on the 926 coach if they want to keep going. The railway runs no further west: you’re heading into the wild.

Anyway, you continue on past Succoth, rounding the head of the loch. The trees on the edge of the road are sparse and through them, you can see an expanse of gentle water and beyond that, a steep vista against the sky. Later, at Ardgartan, the road begins to wind again, curving through dark woodland and out into sunshine. Land falls away on the left and stretches up on the right as you travel further and further into the mountains.

If you look down, you can trace the path of a burn twisting across the valley floor. Sprawling evergreen forests roll like giant rugs over the landscape, while yellow-blooming heathers, punctuated with ferns, tumble down steep slopes. Every now and again, you see a long waterfall in the distance.

The road keeps ascending. Buzzards ride updrafts and hang in the air, while smaller birds flock across the valley. If you want a better look at the Old Military Road meandering through Glen Croe, you can swing into the car park at the famous Rest and Be Thankful. Ahead, Loch Restil cuts a thin trough through the pass.

Next, you drive past Cairndow and on to Loch Fyne, where the asphalt curves around the edge of sparkling water. A while later, you’ll cross a humpbacked bridge and see Inveraray Castle on your right before heading into the town itself.

Occasionally, the big sea loch disappears and you bumble through arable land, but you always meet the inlet again eventually. You’ll pass through Lochgilphead and over the narrow metal Crinan Canal swing-bridge at Ardrishaig, continuing on past Inverneill and Erines and the salmon farm just offshore.

Finally, you descend into Tarbert, where the main street bends around the harbour. Several cafes, a couple of pubs, gift shops, art galleries, a small supermarket, an ironmonger shop, a butcher and a newsagent face the water in a semicircle. Fishing boats enter and leave the sheltered port via a narrow bottleneck several hundred metres away.

Up and out you go, past the parish church and the village hall. You continue along the edge of Loch Tarbert, past the Kennacraig terminal with its big Islay car ferry docked and ready for departure, and on through Whitehouse and Clachan.

Then, suddenly at the top of a blind summit, the overhanging trees give way to a broad landscape and you see the sound of Gigha for the first time, water glimmering blue and green in the sunlight. Jura sits on the horizon, its iconic paps on the skyline. According to local legend, Kintyre’s ancient inhabitants considered the island a mother goddess and erected standing stones on the peninsula to worship her.

As you drive south, Jura’s matriarchal peaks slide behind the northern tip of Gigha. You zip past boulder-strewn croft land covered in tough scrub grass and reeds, and on the shore side, sheep and cows of all colours graze in flat fields next to the ocean.

There are flowers everywhere in spring and summer. Rhododendrons bloom along the roadside, while yellow rock roses, daisies, red clover and purple vetch spill out of ditches and meadows and gaps in stone walls. Shades of green are incredibly chromatic.

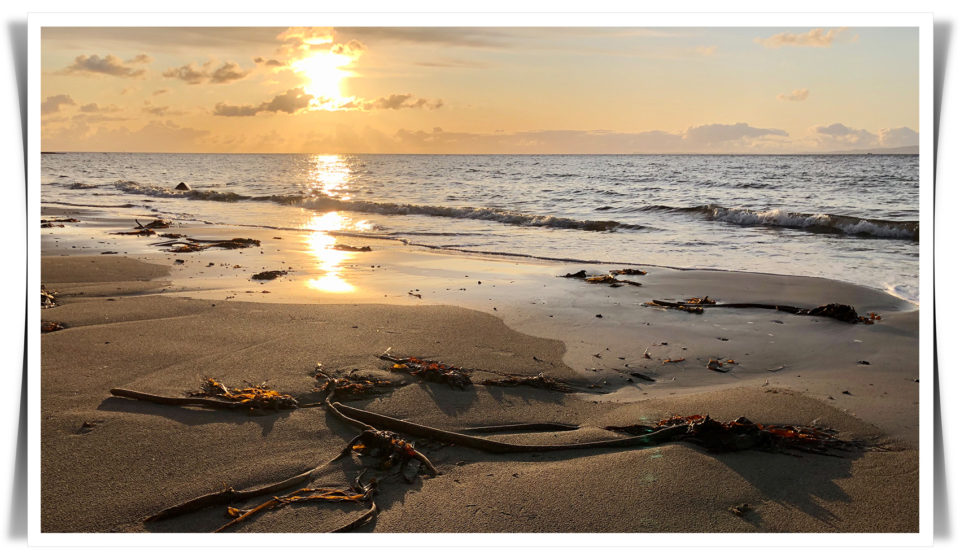

Deserted beaches of pale sand, abandoned stone cottages, old roofless churches enclosed in ivy, clifftop farmhouses and trees covered in thick moss fly by. Seagulls congregate and follow moving tractor plows; robins chase sparrows in and out of bushes at the side of the trail.

If you pull over at Muasdale and walk down to the beach, you’ll see a gigantic weather-worn boulder in the sand. Lemon-coloured marsh marigolds and buttercups, pink vicia, herb robert and bramble flowers spring over the beach border. It’s gorgeous.

And that’s where we’ll stop, because that’s home. That’s where all our adventures begin.